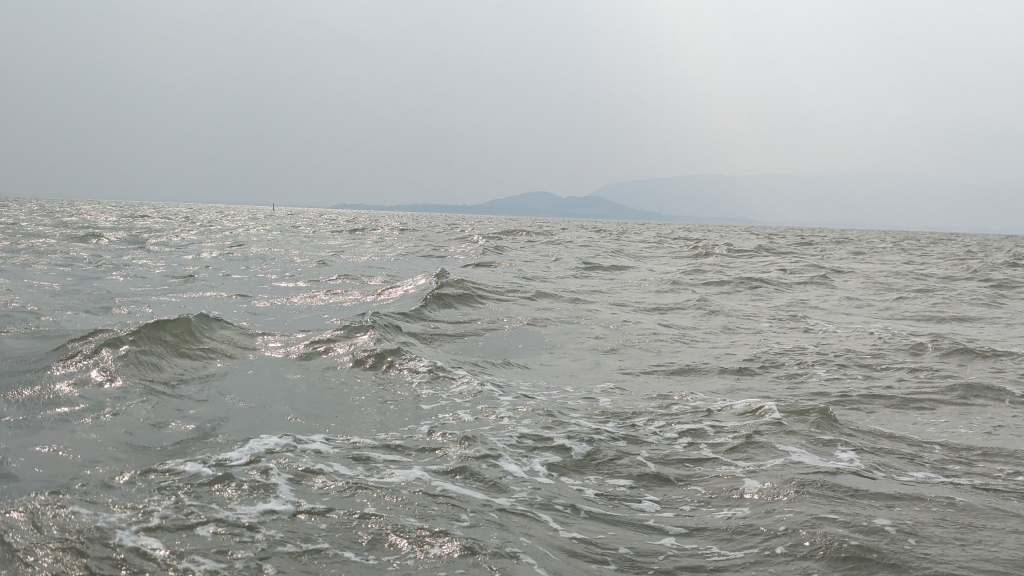

The waves roll and rush around us, silvery-grey, tipped in gold. The lagoon is tumultuous, the skies cloudy enough to bear the promise of rain later in the day. On the boat, we are blissfully enraptured by the water surrounding us. I try to catch a wave with my toe and fail; the boatman calls a warning to hold on as he cleaves through the choppy waters.

Out here in the heart of Chilika Lake, the skies seem endless and the shores are out of sight. We are here for the field module of the first ever six-month Wetlands Ecology, Biodiversity and Conservation certificate course, conducted by the Fishing Cat Project, IUCN Species Survival Commission Freshwater Conservation Committee and Future For Nature Academy, the Netherlands. For 17 days, we will be immersed in learning hands-on techniques in wetland ecology and hydrology, discovering the hidden treasures of Chilika Lake, and learning how to become better informed practitioners and advocates for wetlands.

Chilika Lake is a treasure indeed. This brackish lagoon is India’s first Ramsar wetland, designated on 1 October 1981 by this international commission. Chilika is the world’s second-largest brackish (a mix of fresh and salt water) lagoon, placed right after the New Caledonian Barrier Reef. This wetland has a mouth, or opening, into the Bay of Bengal, which serves as the point where seawater flows into the lagoon and influences its character. You see, one cannot drink the waters of Chilika – it is far too salty. Freshwater inflows are from 52 tributaries of the Mahanadi River in the northern zone of the wetland. The marshy lands at the northern edge are also the home of the elusive fishing cat, one of the most ecologically important and sensitive species found in the lake. I hope I see a fishing cat on this trip!

Our boat rocks gently as we chug along towards Nalabana Bird Sanctuary in the heart of Chilika Lake. This bird sanctuary is in the core area of the Ramsar site. It was declared a sanctuary as part of the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972 and is a wintering ground for many species of migratory birds that spend the cold months in Chilika. In Odia (the language of Orissa), Nalabana means “weed-covered island,” and indeed, seagrass beds can be observed floating just below the water’s surface around the small island in the centre of the sanctuary. Most of the sanctuary is mudflats, which are exposed during the low tide and covered in the high tide. In the monsoon, the entire island and the surrounding mudflats are submerged.

Once we enter the sanctuary’s boundaries, marked by poles in the water and a small red sign, we putter through a series of shallow, curving waterways towards the main island. And that’s when a riot of colours meets my eyes.

Bright patches of pink bob about. Flamingos – dozens of leggy, shockingly-pink flamingos – peck at the mudflats, standing on one leg meditatively while swallowing. These pink birds have made a long journey from Iran and the Rann of Kutch to reach here, and now, at the end of the winter, many flocks would have already returned to their summer grounds. Around them stand other species – lesser flamingos, grey herons, purple herons, spoonbills, storks, Goliath herons, and others – all feeding in the shallow, exposed waters. The mudflats provide a veritable banquet for these waders. I keep my eyes peeled for the white-bellied sea eagle, a large raptor that serves as the main predator at Chilika, but all I see are a couple of ospreys, a few Brahminy kites, and one very loud black kite.

While the left side of the boat is a feast for waterbird lovers, the right side is peppered in smaller black birds. I spot a few glossy ibis and a couple of plovers. Sandpipers, lapwings, and wagtails peck about energetically, and a flock of ducks drifts aimlessly on the shallow water. A herd of Orissa buffalo meander on the grass-covered island, making their way towards the water for a well-deserved drink. The landscape exudes peace despite the cacaphony of so many birds. Somehow, fights are minimal. A small flock of pelicans squabbles with a group of ibises, but otherwise, the waters are calm.

Our boats are moored at the small pier on the island and a forest department official checks our permit. We offboard, immediately dashing up the watchtower to soak in the views. The afternoon sun beats down on our heads, but we are just thrilled to be out on the lake, observing birds and being good field ecologists. The wind is strong here, and hats are almost lost.

The flamingos look tiny from up here, their pink wings folded neatly against their bodies and their long necks set aflame by the sun. A purple heron unfolds its long neck, extending, extending, extending until it reaches its peak length, eyeing a stork suspiciously. The mudflats are alive with busy birds, each pecking about to uncover tasty invertebrates to snack upon.

The sun is setting rapidly, and soon, we will have to board the boats once more and return to the far end of the lake. Maybe another day, we will return to the pink-tinged waters of Nalabana and meet the flamingos and other winter visitors once again. Until then, we stand on the wind-washed watchtower and try to memorize the sight of so many birds gathered in this one special place.